success story

Building a tiny home development in rural Wisconsin

Tiny Timbers Agrihood honors nature and community

Melissa and Shane Jones live in the picturesque community of St. Croix Falls, a city of about 2,200 along the St. Croix River in northwest Wisconsin, a place that’s home to two national parks and all sorts of scenic hiking and cross-country ski trails.

Looking for a way to connect their four children with the more rural experiences of their own youth, the couple bought some property on the city’s outskirts and had a small cabin placed on a plot of prairie surrounded by wildflowers and woods. “It’s a fun place to hang out for a few hours,” Melissa says.

Looking for a way to connect their four children with the more rural experiences of their own youth, the couple bought some property on the city’s outskirts and had a small cabin placed on a plot of prairie surrounded by wildflowers and woods. “It’s a fun place to hang out for a few hours,” Melissa says.

After a few years, they started thinking that the land had space for more than just their little cabin. Maybe others would like to put down roots there and share their love of nature and their care for the environment. Melissa and Shane would create a tiny home community, where dwellers could minimize their environmental footprint and share space as they grew healthy foods, formed friendships, and enjoyed nature.

In early 2022, Melissa and Shane took their proposal to the city. Officials liked the concept, but there was a hitch: St. Croix Falls had no zoning laws on the books to establish tiny home communities. That was the first challenge.

Bringing the vision to life

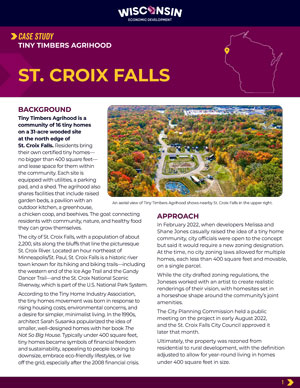

Melissa and Shane engineered a vision: Tiny Timbers Agrihood would consist of 16 sites for tiny homes—each no larger than 400 square feet—surrounding a common area with raised garden beds, a community pavilion, an outdoor kitchen, a chicken coop, beehives, and a greenhouse. Residents would bring their own tiny homes, and the agrihood would provide a parking pad, a shed, and connections to city utilities.

Most of the 140-acre site was zoned as residential, but the agrihood didn’t meet that definition. Rural development zoning—which governed operations such as campgrounds—was a better fit, but the definition had to be adjusted to allow for year-round residents and to set some minimum standards for the tiny homes, which fall under the rules governing recreational vehicles due to their size.

Meanwhile, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) rules required a stormwater retention pond to be built. But when backhoes dug into the ground at the chosen spot, it was too thick with clay. To meet DNR standards, engineers called for cutting down two football fields worth of old-growth sugar maple trees to make room for the retention pond. Melissa and Shane nixed that idea. Instead, a different site was chosen with more sandy soil, but it, too, had challenges: it slanted uphill. Moving earth and regrading the land added to the time and cost of preparing the site.

Even so, by June 2023, Tiny Timbers was ready to open. Within 15 months, all of the sites were occupied. Residents include a doctor, teachers, and a therapist; there are single men and women, couples, and a mom with two young children.

It is believed to be the only year-round, rural, tiny home community in Wisconsin.

City water and sewer service was extended to the property and electrical lines, natural gas, and fiber optic internet service were installed. “We built it to regular, residential standards so that if, for example, the development ever had to be transformed to other types of housing in the future, that could be accomplished without redoing everything,” Melissa says.

Residents own their small homes and they don’t have to pay property taxes. The city charges a minimal PILOT (payment in lieu of taxes) fee to cover police and fire protection, emergency services, and general city administration, and homeowners pay $495 a month to rent their space and share community amenities.

It is a form of affordable housing for like-minded people.

“Our ultimate vision is to help people live their best life there,” Melissa says.

Take a more in depth look

Watch a video

Inspiring creative housing

Tiny Timbers has now gone through its second winter. The retention pond froze over and residents used a handheld Zamboni to create a skating rink. Shane groomed the trails for snowshoeing and cross-country skiing—until the mild weather melted the snow.

With spring’s arrival, the chickens are “dust-bathing and scratching all over in the orchard,” Melissa says, while migrating birds are “eagerly starting their nests in the boxes the community painted and hung around the pond and garden. The bees have been very active, already collecting pollen from budding maple trees.”

Tiny Timber residents standing by the community garden.

Melissa and Shane hope their tiny home community can serve as a model for other types of creative housing developments. “For example, when a farmer sells to a residential developer, instead of bulldozing the farm, it could instead become the heart of the community, allowing residents to participate and have a deep-rooted connection with where their food comes from,” Melissa says.

In larger agrihoods, often there’s a farmer on site who handles most of the operations, and residents can volunteer to help with the gardening. The farmhouse can even function as a community gathering place, she says.

For now, there are no immediate plans to expand Tiny Timbers, though there’s space available on the property. “We are also still perfecting phase one and taking a little breather. We haven’t crossed that bridge just yet,” Melissa says.

“Our ultimate vision is to help people live their best life there.”